Remember those movies about some kind of technical sabotage or virus that wreaks havoc on the world, causing a multitude of negative consequences. Well, a similar scenario, though unintentional, took place in 2024 when CrowdStrike (a NASDAQ listed company) crushed the systems of tens of thousands of its customers and found itself in the middle of a global crisis.

In the aftermath, there have been different opinions (1, 2, 3, 4) on the Internet regarding the company’s response to the crisis from a communications perspective. The majority seems to believe that the company did well. Unfortunately, we do not agree with that. It would be fair to say that CrowdStrike failed at the beginning but got better during the crisis, adjusting its strategy and corresponding actions. But if to evaluate the situation as a whole, taking into account that it is a cybersecurity company with USD 70-80 billion capitalization and necessary resources at hand, Crowdstrike could have done better. Today we’ll review this case and back our arguments in more detail.

Overview of the company

CrowdStrike is a leader in endpoint security, focuses on preventing and detecting complex threats. Its platform uses the cloud technology, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to fight a variety of cyber-attacks in real-time. Endpoint security aims at the protection of individual devices, such as laptops, desktops, and mobiles, from malicious incursions.

More than half of Fortune 500 companies currently opt for CrowdStrike's security products. According to CSO, CrowdStrike ranks sixth on the list of most powerful cybersecurity companies in the world.

CrowdStrike Falcon is an Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) software solution that monitors end-user hardware on a network for suspicious activity. It automatically blocks perceived threats and logs forensic data for future investigation

Like all EDR tools, CrowdStrike Falcon gives total visibility into activities occurring on an endpoint device, including processes, registry changes, file and network activity. It connects that data visibility with analytics ML/AI capabilities to defend customer’s systems through automated actions or human oversight.

The root cause of the outage

CrowdStrike explained that it had released a "buggy content update" to its Falcon EDR platform, which was pushed out to Windows machines at 04:09 UTC (0:09 ET) on 19 July, 2024. Usually, updates to the Falcon endpoint sensors, coined as "Channel Files", happen several times per day automatically, i.e. it does not require end-user authorization per-se.

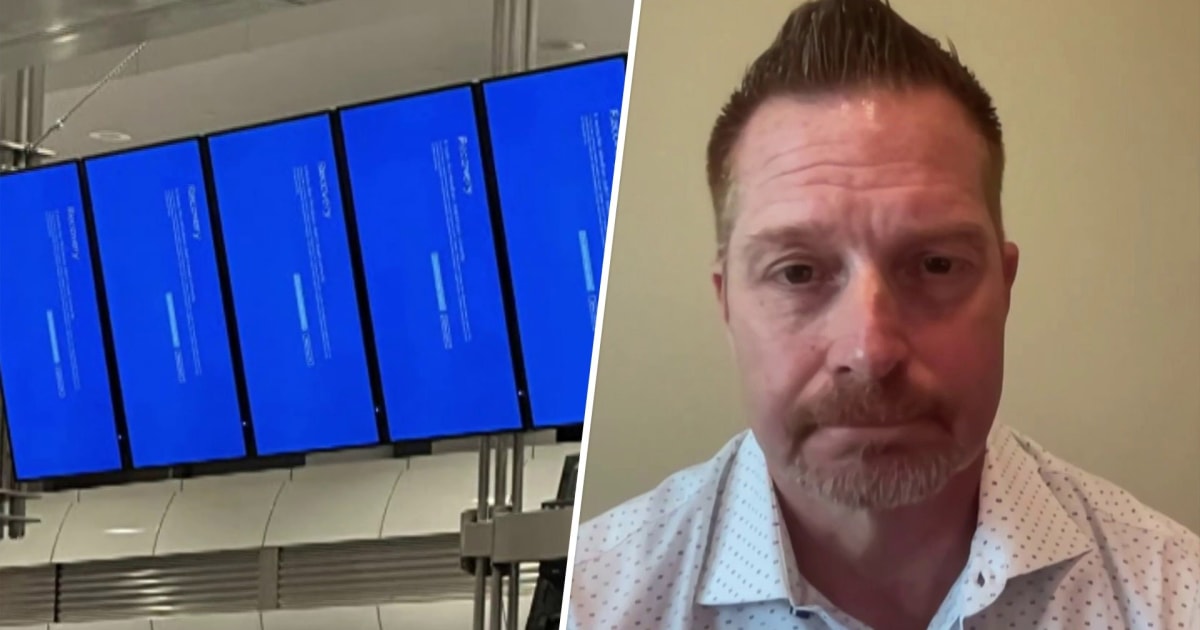

A malformed "Channel File 291" file, part of the Rapid Response Content update package, caused a logic error in the Windows system, resulting in a continuous loop of operating system reboots ('blue screen of death').

By 05:27 UTC on 19 July 2024, that is 78 minutes later, CrowdStrike had identified the bug and rolled back the changes, but by then many systems were already down. The update affected Windows 10+ versions without having any impact on the Mac and Linux systems as they have different software architectures.

It wasn't an issue or vulnerability with Microsoft Windows itself but rather a faulty file with CrowdStrike Falcon that caused the crash. Falcon is a Windows kernel process running with high privileges to monitor system events in real-time. In layman's terms, when a traditional application (let's say Microsoft Word) working on top of Windows malfunctions, it does not affect Windows itself. But CrowdStrike Falcon is a kernel process, meaning it is a part of Windows, and when it malfunctions - it affects the whole operating system.

The consequences of the outage

Microsoft estimated that the update affected about 8.5 million Windows computers which is less than 1% of the number of Windows computers worldwide. Dave DeWalt told on the Dow Jones' podcast "On Watch" that 30,000 CrowdStrike customers were directly affected and another 674,000 indirectly. It was enough to destabilize many client computers and servers in different industries.

To put it into perspective, around 3,000 flights within, into, or out of the US were cancelled and over 11,000 flights were delayed on July 19. Due to continuing problems cir. 2,500 more flights were cancelled and around 38,000 were postponed three days after the outage. Healthcare also suffered seriously, with operations delayed, 911 dispatches out-of-service, and clinicians being forced to revert to using paper charts as they could not access their electronic health records.

Financial losses are still being calculated, but Derek Kilmer of Burns & Wilcox estimated that insured losses could reach $1 billion or more. Losses were pegged at $5.4 billion by insurer Parametrix for US Fortune 500 firms alone, excluding Microsoft.

Delta Airlines, having processed over 175,000 refund requests, hired attorney David Boies, who led the U.S. government's antitrust case against Microsoft in 2001, to seek damages from CrowdStrike and Microsoft. Delta's financial hit from the outage is estimated at $500 million. CEO Ed Bastian said Delta had to manually reset 40,000 servers and will "rethink Microsoft" for its future operations.

Meanwhile, CrowdStrike is being sued in a class-action lawsuit by shareholders, , who allege the company defrauded them by not disclosing weaknesses in its software validation process, which then caused the outage and a subsequent plunge in market value by 32% or $25 billion.

Eventually, the US Congress representatives Mark Green and Andrew Garbarino wrote a letter to George Kurtz, CEO of CrowdStrike, asking about the incident and CrowdStrike's mitigation strategies. To quote “[Americans] deserve to know in detail how this incident happened and the mitigation steps CrowdStrike is taking”.

George Kurtz, CEO. Photo: Kate Dingley / Bloomberg

The CrowdStrike’s Crisis Communication

There are a few things we must bear in mind before critically assessing the CrowdStrike communications strategy execution:

(i) CrowdStrike’s CEO, George Kurtz, was previously the CTO of McAfee, another top cybersecurity company. During that time in 2010, he experienced a similar outage crisis as with CrowdStrike, but to a lesser extent, impacting thousands of customers and leading to BSODs.

(ii) CrowdStrike advises its customers how to prepare for incidents and publishes relevant [quite good] checklists, including steps on crisis communications.

(iii) CrowdStrike is a cybersecurity company with a billion-dollar budget at hand. We believe, it is expected of them to be more prepared for incidents than any other traditional corporate entity.

Given these points, let’s examine CrowdStrike's response to the outage in chronological order with our comments.

(A) Once the news of the outage hit the Internet, George Kurtz, CEO, published the first message on Twitter (X) at 02:45 AM Pacific Time, 19 July 2024:

George Kurtz’s first message posted on X after the news of the outage caused by CrowdStrike software. Source: https://x.com/George_Kurtz/status/1814235001745027317

We see several issues here. The key issue is that, evidently, CrowdStrike did not have a prepared crisis response strategy and communication hub (with at least some 'holding' statements) in place, even though they kind of teach it to others. It is highly likely that Kurtz’s message was written by a representative of the legal team. It lacks the touch of a crisis manager at all and an understanding of what the first message is supposed to achieve, even if it is just a holding statement. The message did not contain any acceptance of wrongdoing or a proper apology.

FYI, a holding statement is a brief pre-planned fill-in-the-blank template for the crisis team to complete with an explanation of what is going on before the team can understand the situation better, check the facts, and issue a more thorough announcement.

Going a bit more granular on the message:

(i) “CrowdStrike is actively working with customers impacted by a defect found in a single content update for Windows hosts” – Kurtz does not confirm that the outage was CrowdStrike’s fault (update), though at that moment, they knew it 100%. This interpretation misleads the customers because it is not clear whether 'a defect found in a single content update for Windows hosts' refers to the Windows update (which, for example, conflicts with the CrowdStrike software), CrowdStrike’s update (which might conflict with the Windows OS), or any other software.

(ii) “This is not a security incident or cyberattack”. How is this not a security incident if tens of thousands of CrowdStrike’s clients were down without a proper defense solution in place? If they wanted to separate the security incident caused by an external actor (e.g., hackers) from a security incident caused organically (e.g., as was the case), they should have noted that by stating, for example, “The root cause of the incident is not connected with any external cyberattack or security breach but due to [specifics].”

(iii) “The issue has been identified, isolated, and a fix has been deployed.” If the issue had been identified already, they should name and clarify the issue. It is also unclear what they mean by “a fix has been deployed” – does this mean the systems will start working? Is there any timeline for the fix to take effect?

(iv) “We refer customers to the support portal for the latest updates and will continue to provide complete and continuous updates on our website.” This really stands out. Basically, they say, “go to our portal, click the 'Refresh' button, and expect updates from us on how to solve your system’s crash.” Try saying this in plain English to 911 dispatchers with dysfunctional systems that should be able to do their job properly (literally “save people’s lives”). We would recommend taking an active position and advising that they “will contact all customers that need individual help in order of priority, starting with medical and health institutions, critical government facilities…” and so on, so that the incident has minimal effect and disruption, along with regular updates on the website.

(v) “We further recommend organizations ensure they’re communicating with CrowdStrike representatives through official channels”. This is similar to the above-mentioned, pushing responsibility for the speed of the fix onto their customers. What channels? What if the channels are packed with inquiries from many customers around the world? What to do in this case?

(vi) “Our team is fully mobilized to ensure the security and stability of CrowdStrike customers”. This is just a usual bland statement, not well-suited for the depth and scale of the crisis at hand.

To draw a line, the first message is almost completely in a passive voice, with no acceptance of responsibility for the situation or apologies whatsoever, and in bland legalese interpretation. As the main character of Hugh Grant says in the British TV series “A very English scandal” – “this is very, very, very disappointing.” (c).

We understand that the crisis was a big one, and the top team and CEO felt immense pressure, but Kurtz could have done significantly better, shown leadership, and not hidden behind some vague release. We would like to believe that those experts, stating that the Kurtz’s only critical mistake here was a lack of an apology, just performed a poor situational analysis at the time.

(B) George Kurtz, CEO, published a second message[1] on X (Twitter) about 5 hours later on the same day 19 July, 2024.

George Kurtz, CEO, published a second message on X in connection with the outage. Source: https://x.com/George_Kurtz/status/1814316045185822981

Kurtz and his team appeared to see the negative feedback after the first message and adjusted the second one. Whether this was done on their own or with the assistance of PR consultants, we do not know. The second message had a couple of similar sentences ("messages" in the sense of constructing a narrative) to which they decided to stick. Specifically: “Today was not a security or cyber incident,” “the issue has been identified and a fix has been deployed” - nothing new here.

He did not add any clarity to the timeline of the remediation process but invited all interested parties to check the newly created “Remediation and Guidance Hub: Channel File 291 Incident.” This was a good decision, aggregating all necessary information (technical details, remediation steps, later FAQs) concerning the outage in one place/hub. Kurtz expanded a bit on the roots of the outage, referring to the Falcon content update, and this time expressed his apologies.

Prompt acknowledgment is critical in crisis management. It enables the company to reduce speculation and rumors, and to provide stakeholders with a clear accounting of what occurred. As they say, language matters; words must be selected carefully, especially under heavy duress. Thus, the phrase “sorry for the inconvenience and disruption” still does not resonate well. With all due respect to the Crowdstrike team, but “inconvenience” is staying in the line for 20 minutes to get a Chick-N-Fill burger. Failure to operate critical patients in ISUs, for example, is a severe crisis. “Disruption” is a better choice, though.

From now on Kurtz started posting the same messages as on X (Twitter) or with minor modifications on LinkedIn. In turn, Crowdstrike’s corporate account on X and LinkedIn made reposts of George Kurtz’s posts.

A team behind a corporate CrowdStrike account on X reposted George Kurtz’s messages on the first day of the crisis.

(C) On the morning of July 19, 2024, George Kurtz gave two short interviews to the Today show and CNBC's Squawk on the Street with Jim Cramer. Kurtz expressed his apologies, explained the situation, and emphasized his key messages (not verbatim): “The outage was not caused by a cyberattack,” “We fixed the issue and rolled back the changes,” “We are working with customers to get all of them online and stable as soon as possible,” and “We do not want to think about legal repercussions at this moment, as our primary goal is to get all customers back online.”

One may notice a change in the narrative compared to the previous text messages, suggesting a sentiment of “yes, we messed up” (though it was not explicitly stated). As you’ll see next, this "change" would be further reflected in Kurtz’s subsequent posts on X and his official open letter.

Afterward, other news channels and portals used these interviews for their own programs and news segments. We must commend the CrowdStrike team for their work in arranging early morning slots on the TV shows. We reckon they worked all night to handle a myriad of inquiries from all sides during the first hours of the crisis. The objective of the morning interviews was quite clear: to address the issue as soon as possible, to reach their customer base and those affected to the fullest extent, and, of course, to reduce stock price volatility.

(D)On the same day 19 July, 2024 George Kurtz posted a third message on X (Twitter)

A third message posted by George Kurtz on X on 19 July, 2024. Source: https://x.com/George_Kurtz/status/1814388276486136251

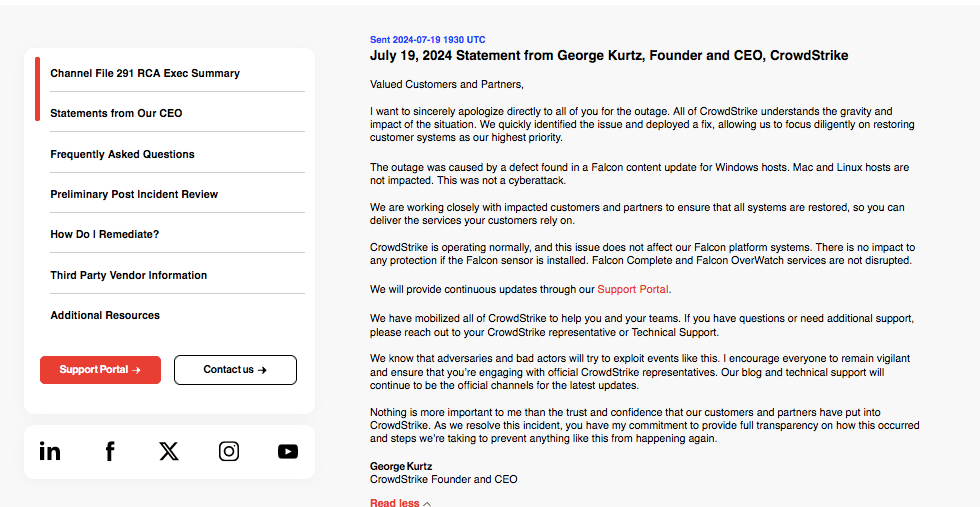

Within the hours the team also posted a more detailed “Statement from Our CEO’ on the CrowdStrike official website under the Remediation & Guidance Hub.

A George Kurtz’s statement published on the CrowdStrike’s corporate website

At this point, one can notice a significant improvement in the content of the open letter and the overall narrative compared to the previous messages. Kurtz used an active voice more frequently, with apologies in the first sentence, and without phrases like "Today was not a security or cyber incident." However, the message still lacks a timeline for a full recovery. It is not perfect, but it is a working statement at last. This was supposed to have been version 1 of the message, not the 3rd or 4th attempt.

(E) Kurtz published the fourth on X (Twitter) on 20 July, 2024. By the way, it was Kurtz's last message on X, as he stopped updating his X account.

The fourth message of George Kurtz on X in connection with the outage and the last message whatsoever on X. Source: https://x.com/George_Kurtz/status/1814467184367673774

This was a simple update to give a heads-up to customers or interested parties that the team had prepared a technical incident review.

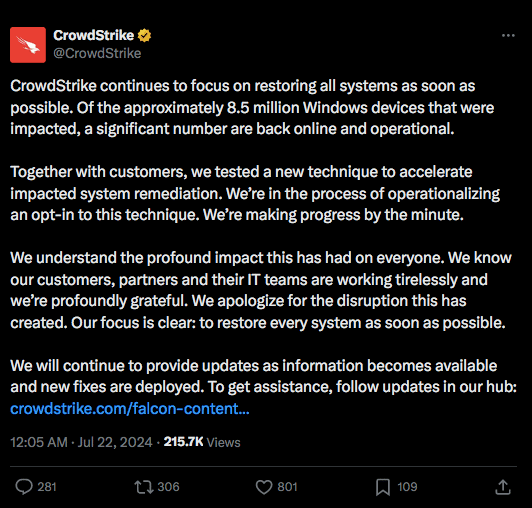

(F) Corporate updates to continue.

With each new communication piece, CrowdStrike strove to adjust the message and wording in response to the feedback they had received earlier from their customers or the broader audience.

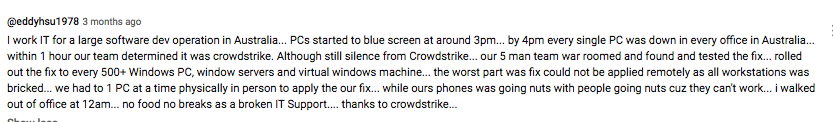

For example, “Together with customers, we tested a new technique to accelerate impacted system remediation. We’re in the process of operationalizing an opt-in to this technique.” First off, it is a bad phrasing. Do you think an ordinary system user would understand the 2nd sentence? Likely, only the affected customer’s server/IT staff really understood. Specifically, to restart the crashed servers and networks, CrowdStrike clients often had to do so manually. During TV interviews, Kurtz mentioned that to apply the fix, customers needed 'just to reboot the systems,' but it was not that simple. See a screenshot of customer feedback below to understand the scale of the manual work in certain cases:

A comment posted by some user on YouTube under the George Kurtz interview.

In an attempt to accelerate this process for customers, CrowdStrike came up with a possible solution. Good for them—no irony here. It was needed, and they tried to deliver.

“We understand the profound impact this has had on everyone. We know our customers, partners and their IT teams are working tirelessly and we’re profoundly grateful. We apologize for the disruption this has created. Our focus is clear: to restore every system as soon as possible.” We can see here how they made almost a complete turnaround in their communication language and overall message. Sure, this should have been done from the start, but at least they are reflecting on their mistakes. It's always a valuable experience to ponder.

On the third day, the CrowdStrike team posted an instructional YouTube video for end-users on how to rectify the outage consequences remotely. It was a do-it-yourself type of video.

(G) A bit later on the same day, 22 July, 2024 CrowdStrike's Chief Security Officer, Shawn Henry, published a long, heartfelt open letter on LinkedIn.

It is a good example of leadership and having guts. It is unfortunate that Kurtz's communication in the initial hours and days following the crisis led to negative feedback and even anger among many customers and affected individuals. Now, even the CSO had to step in to soothe public opinion. Whether the CrowdStrike execs and a board intentionally “encouraged” Shawn Henry to step in with his message to share the responsibility for the outage with George Kurtz , we do not know and do not wish to speculate. Let's leave it as is.

One more thing we would like to mention is how CrowdStrike messed up a bit with their Uber Eats gift cards. As it was reported CrowdStrike offered a gift card to its partners and teammates who have been helping customers to cover their “next cup of coffee or late-night snack,” due to “the additional work that the July 19 incident has caused.” One X user posted that the email was sent by Daniel Bernard, the CrowdStrike Chief Business Officer. In its response, the company representative said that they “did not send gift cards to customers or clients. We did send these to our teammates and partners who have been helping customers through this situation. Uber flagged it as fraud because of high-usage rates”. Whatever good intentions they had at that moment, it did not matter anymore, as they faced backlash from the public for an 'inadequate' response. It turned out that affected customers received those gift cards and did not 'appreciate' (we can concur with them on this, to be honest) the 'gift' after what had been done by the outage.

Final Remarks

What went wrong with Kurtz's first attempts at public statements was that he did not clarify well enough the root cause of the incident and how they would rectify the situation. He also failed to apologize at all. A genuine apology to key stakeholders is crucial. Effective leadership acknowledges issues, accepts responsibility, pledges to assess what went wrong, and commits to prevent future incidents.

Although some people hounded Kurtz only for not including an immediate apology in the initial communication, we cannot agree with that assessment. The customers needed to know the steps that would have made the outcome more predictable for them.

The CrowdStrike team moved fast in terms of crisis management, and everyone must commend them for it. As we discussed earlier, they made big mistakes at the beginning but got significantly better by the end of those 3-4 days of the crisis. Likely, the company seized the services of external crisis consultants on the first day of the crisis, seeing that the executive team needed assistance.

They used all available platforms, news outlets, and social media to try to reach as many affected customers as possible. Kurtz handled his media appearances calmly, he avoided using technical terms and did his best to speak in simple terms. He took responsibility and provided a reasonably detailed explanation of the problem, while emphasizing the complexity of managing large-scale cybersecurity outages.

Notwithstanding the communication language, the strongest part of CrowdStrike's response was their customer-focused approach. Kurtz and Henry put customer security and operational continuity front and center with a promise that all resources were assembled to quickly resolve the situation. This type of outreach does not buy forgiveness, but it does signal to the most important audience that the team is hard at work until it is solved. Unfortunately, the effort did not appear to be enough, as there was a continuous flow of confused inquiries and comments from customers all over social media. We are sure that the CrowdStrike team saw this as well and expanded their bandwidth to provide more assistance.

Sending a $10 Uber Eats gift certificate as an apology gesture was tone-deaf and did not help to recover their image. Whatever good intentions the team had at the moment, the customers and audience did not appreciate it, given the gravity of the situation.

A crisis is rarely well-received, but better planning could have eased some problems. CrowdStrike should have had a crisis communication plan in place, which is the very thing they advise their customers to do. Today, executives must be prepared to talk directly to consumers in plain terms, as the time of press releases has come to an end.

In similar situations, while the crisis experience is not yet settled, the company must conduct a swift post-crisis evaluation of everything that was done and its effectiveness. The key questions the leadership must answer are: “Are there any other similar risks in place?” and “What will be done differently if something like this happens again?”. To the best of our knowledge, CrowdStrike published a Preliminary Post Incident Review and External Technical Root Cause Analysis.